Speech to the Virginia Bankers Association. Richmond Convention Center. January, 10, 2019.

Thank you for inviting me today. It is not every day that a college president gets the opportunity to address a group of bankers, so I’ll make sure to use the privilege wisely—lest I be the last one you invite!

To provide some context to my remarks, let me tell you a little bit about George Mason University.

Mason is Virginia’s largest public university, Virginia’s fastest-growing university, one of Virginia’s four tier-1 research universities (the other three are UVA, Virginia Tech and VCU) and the nation’s youngest tier-1 research university (there are 130 of them). We serve one of the most diverse student populations in the nation. Among our almost 38,000 students, about half are minority. Almost 40% of our undergraduates are the first generation in their families to get a college degree and almost 30% qualify for Pell Grants, the federal need-based financial aid program. We also receive more community college transfer students than any other university in the Commonwealth.

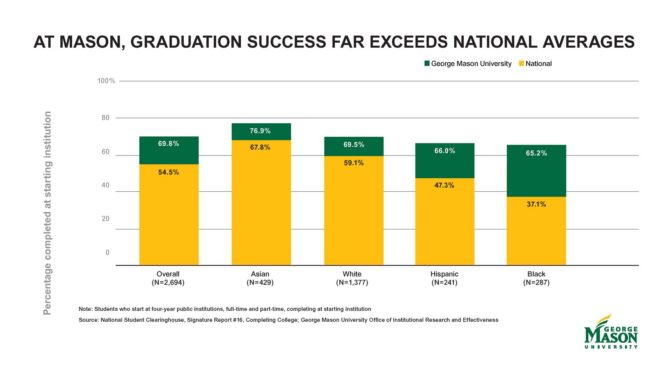

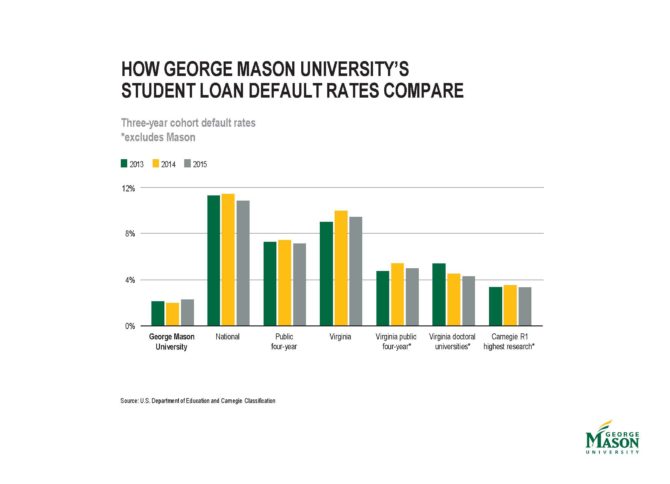

Graduation rates at Mason are 15 percentage points higher than at the average public university and they show little variation across ethnic or income groups. Also, our student loan default rates, a good metric of ROI, sits at 2.3%, compared to a 7.1% national average for public universities.

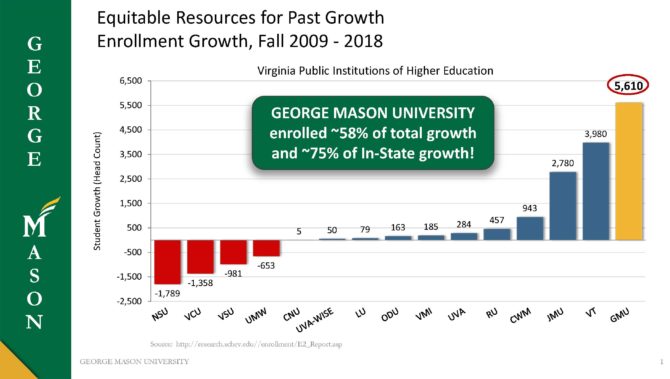

We see our mission as providing access to excellence. While we pride ourselves on being ranked among the world’s top 300 universities and having earned the Nobel Prize on two occasions, and while we compete toe-to-toe with top universities for federal research awards, we remain fully committed to providing access to as many students, from as many backgrounds, as we can help learn and grow. That is why, over the past decade, Mason has accounted for about 58% of all the growth in enrollment in Virginia.

We see our mission as providing access to excellence. While we pride ourselves on being ranked among the world’s top 300 universities and having earned the Nobel Prize on two occasions, and while we compete toe-to-toe with top universities for federal research awards, we remain fully committed to providing access to as many students, from as many backgrounds, as we can help learn and grow. That is why, over the past decade, Mason has accounted for about 58% of all the growth in enrollment in Virginia.

I realize part of the reason you invited me here today is because I serve on the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. As directors of the bank, in addition to our usual fiduciary responsibilities, we regularly share our views on economic trends in our region with the bank’s president, Tom Barkin, and his research team. I, however, do not represent the Bank or the Federal Reserve in any way, and all the views I’ll share with you today are mine alone.

As you know, the U.S. economy is currently quite strong. During the third quarter of last year, GDP was growing at 3.4%, unemployment was at record low levels—under 4%–and real interest rates, even after the recent adjustments are still very low—the Federal Funds Rate is just barely above inflation. And yet, to the amazement of some of my economics department colleagues, inflation is right at the Fed’s 2% target. What’s not to like!

I know the million dollar question, or perhaps the 100 billion dollar question, is how long will the party last? Are we due for a correction?

I’m afraid I don’t know the answer to that question. What I do know is that, over the long run, the economy grows when more people work and when they work more productively. Higher education is critical to both. People with college degrees work at higher rates than people without degrees, they are more productive than people without degrees, and they are more likely to drive innovation and entrepreneurship that can help create more jobs and push productivity further. Universities are not just important for economic growth, they are essential.

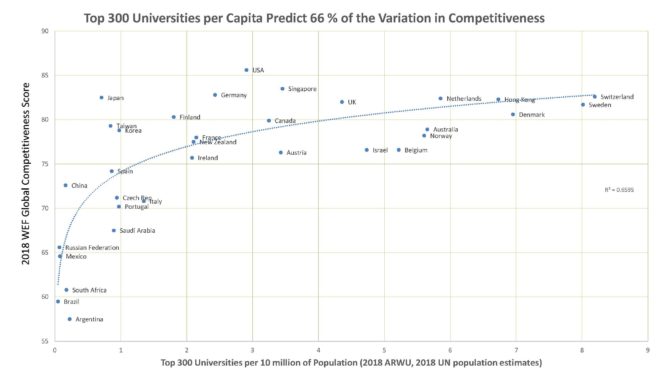

Consider the following chart. Each dot represents a country. The bottom axis shows how many universities that country has in the top 300 in the world, according to the Academic Ranking of World Universities, normalized by its population. Switzerland, for instance, has a little over eight elite universities per 10 million people, which is the highest concentration in the world. The U.S. has about three, and my home country of Spain, one. On the vertical axis you have the country’s competitiveness score as calculated by the World Economic Forum, which is intended to be an estimate of the country’s prospects for long-term growth. As you can see, the relationship between the concentration of elite research universities and competitiveness is quite strong. In fact, universities alone in this simple model account for two-thirds of variations in competitiveness.

So it is not surprising that, when Google decides to create a major software engineering in Europe, it would do so in Zurich, Switzerland. Not the cheapest place to live, nor the warmest or most fun. But it’s the home of ETH (Europe’s MIT) and the University of Zurich, both ranked in the top 300, and a short train ride from five other universities in the same category.

Similarly, when Amazon decided to create a new hub in the U.S., it made sense that it would choose Northern Virginia. In addition to George Mason, University of Maryland, Georgetown and George Washington University in the DC metro area, all of which are listed in the top 300, you have Johns Hopkins, University of Virginia, and VCU within a short drive, and plans by Virginia Tech to grow their presence in the region. If you carve out the broad region spanning Baltimore to Richmond, what some have begun to call Greater Washington, and plotted it on that chart, Nation Greater Washington would be right there alongside Denmark and Hong Kong and not far from Switzerland.

Dirty little secret: It is not tax incentives that attract leading companies, though incentives they will seek. It is a rich supply of smart people that attracts leading companies. And that’s precisely what universities are great at. Universities attract talent. They produce talent. And they spin out ideas and innovation.

As per attracting talent, consider the following statistics. The Kauffman Foundation reports that immigrants are key to our nation’s entrepreneurial fabric. Immigrants account for almost 30% of all new entrepreneurs in this country. Twenty years ago, that number was 13%. This increase not only reflects the growth of the immigrant population but the fact that entrepreneurs are about twice as likely as native-born Americans to start a business. The numbers are even more striking if you look at the most successful startups. According to the National Foundation for American Policy, 50 of 91 American startups valued at $1 billion or more were started by immigrants.

A few years ago, the Kauffman Foundation asked what had brought these immigrants to the U.S. in the first place. In more than half of the cases, it was higher education. Every year, more than a million young, talented people come to this country to study. Many will return to their country of origin, but some will stay. Among them we’re likely to have the founders of the next Uber, Tesla or Palantir, and the next CEOs of Google or Microsoft. Let alone hundreds of thousands of professionals and engineers powering America’s most competitive and innovative companies.

Unfortunately, this year, for the first time since 9/11, the number of new foreign students coming to the U.S. has declined. The administration’s negative and even hostile narrative around immigration, the travel ban affecting students from certain Muslim countries, and other policies, are not helping our case. Meanwhile, Canada is making it easier for foreign nationals to not only study in Canada, but to stay and contribute to their economy. Not surprisingly, while our numbers decline, theirs are up—20%!

Regardless of where students come from, universities play a role as sources of educated, highly productive talent. The impact that higher education has on productivity and economic outcome cannot be overstated.

Consider the five states with the highest university achievement numbers: Massachusetts, Colorado, Maryland, Connecticut and New Jersey, all between 37% and 40% of adults with a college degree (in case you wonder, Virginia would rank sixth at 36%). Consider also the five states with the lowest achievement numbers: Louisiana, Kentucky, Arkansas, Mississippi and West Virginia, with participation rates between 19 and 22%. The most highly educated states have an average per capita income of more than $70,000 dollars. The lowest educated states, meanwhile, only $43,000.

A college degree today is as strong a predictor as it gets of your ability to get a good job with good benefits, of your overall health and even your longevity. And the value of a degree, not just for your community but for you personally, is not shrinking but widening. The data remain stubborn: going to college is one of the safest investments you can make, even if you have to borrow money to do it. Don’t pay too much attention to the pundits who argue that college education is overvalued and that not everyone needs one—chances are they went to fine schools themselves as will their children if they possibly can.

What should concern us is not whether we are educating too many people — no society has ever failed for overeducating — but how we can manage to educate even more. What are the barriers that still exist for many to get educated and what can we do to overcome them? At Mason, we’ve developed a partnership with Northern Virginia Community College, called ADVANCE, to make the process more seamless for students to transfer and earn a four-year degree while saving money.

We’re also developing online programs, in partnership with Old Dominion University and others, to help working adults finish their degrees. There are tens of millions of such adults in the United States, who don’t fit the traditional mold of a college students and who have traditionally been ignored by universities.

Further, universities, especially in the United States, are catalyzers of innovation. Since World War II, the United States has relied on its universities as laboratories of basic and applied research. While universities are not the only places where research takes place, they are the main hubs, both as magnets and sources of talent, and as major research contractors for the federal government.

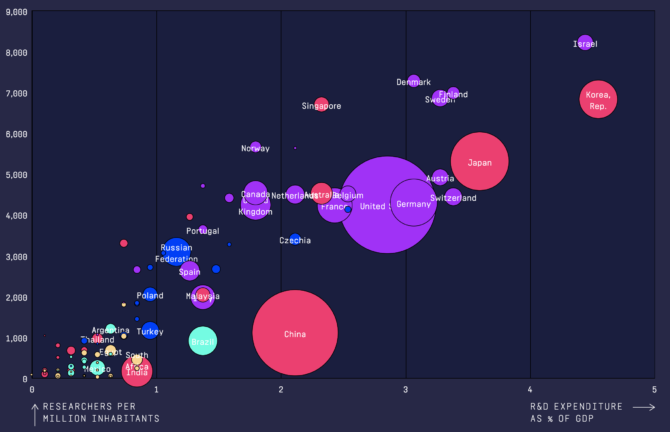

The United States remains the largest investor in research and development in the world, but the concentration of those investments is far from uniform, and, when factoring in the country’s population and economic magnitude, we are not the world’s leader. Korea, Israel, and Japan, for example, spend more, both in share of GDP and share of labor.

I won’t get into tax policy here. I realize the cut in corporate tax rates has been celebrated widely by businesses and I recognize the immediate impact they can have in incentivizing domestic investment. My concern is that, as the budget deficit continues to balloon, there will be a day of reckoning when tough decisions will need to be made on the spending side, and research may be too easy a target to ignore. I hope we remember that without major research investments there would be no Internet, no genomics, no lasers, no AI and no space industry. Or those advances would be made elsewhere.

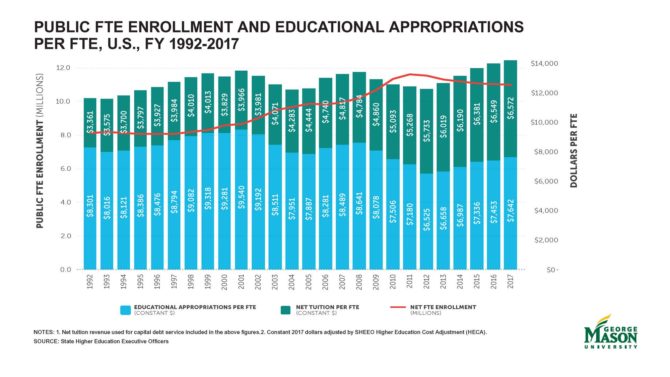

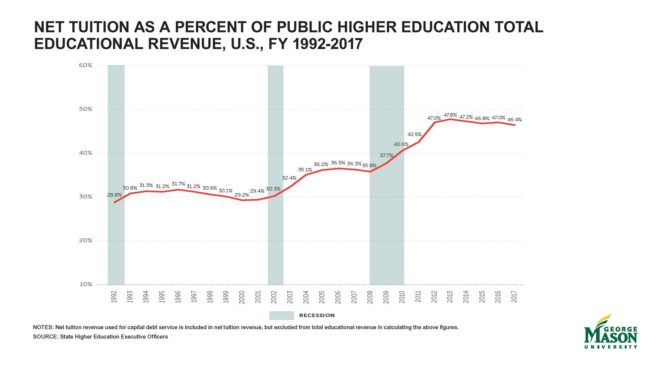

The last 20 years have not been great in terms of public investment in higher education. In constant dollars, appropriations per student have declined, therefore transferring the financial burden to students in the form of higher tuition and higher student debt. Today, more than 44 million Americans have student loans, totaling a record $1.5 trillion. From an individual standpoint, borrowing to go to school remains the smart, rational choice to make, if one does not have sufficient family wealth. But, as a society, we must carefully examine the multi-generational implications of this dynamic — impact in home ownership, in savings rate, in the capacity to support the education of one’s children.

When I first landed in the U.S., as a Fulbright scholar from Spain, I was amazed at the resources of the American university. I assumed this was a sign of wealth. America, I thought, had those beautiful, well-endowed universities because it was rich enough to afford them. Over time, I have concluded I got it backwards. America does not have great universities because it is economically prosperous. It is economically prosperous because it built great universities.

When I first landed in the U.S., as a Fulbright scholar from Spain, I was amazed at the resources of the American university. I assumed this was a sign of wealth. America, I thought, had those beautiful, well-endowed universities because it was rich enough to afford them. Over time, I have concluded I got it backwards. America does not have great universities because it is economically prosperous. It is economically prosperous because it built great universities.

As I warned you, I have no answer as to the immediate direction of our economy. What I do know is that, over the long run, investing in our great research universities is one of the smartest and safest things we can do.

Thank you for having me today. I would be happy to address any questions you may have.