By Ángel Cabrera and Kirk Heffelmire

In the end, our state appropriation was not cut by 5%, as it was originally announced, but by 3.8%. Across the Commonwealth, higher education will see, on average, a reduction of 3.3% in state support a consequence of the tax revenue shortfall Virginia faces.

This reduction in funding is not an isolated event. As we’ve discussed here before, it is a new data point on a 15 year-long trend of reduction in state funding of universities, not just in Virginia, but across the country. One of the most direct consequences of this trend has been a dramatic rise in tuition. In our case, inflation-adjusted expenditures per student have not changed noticeably, but our state appropriation per student has effectively been halved and our tuition has consequently more than doubled. In short, we have moved from a model that sees higher education as mostly a public good that is primarily funded by the state, to a model that sees a college degree as mostly a private good to be primarily paid for by the student.

One of the most direct consequences of raising tuition is the ballooning of student debt. Recent college graduates hold the highest student loan debt burdens ever. The majority of students graduate with at least some loan debt. In Virginia, the number of undergraduate students graduating with more than $25,000 in loan debt more than doubled between 2008 and 2012. The average debt per Virginia college graduate in 2012 was well over $18,000.

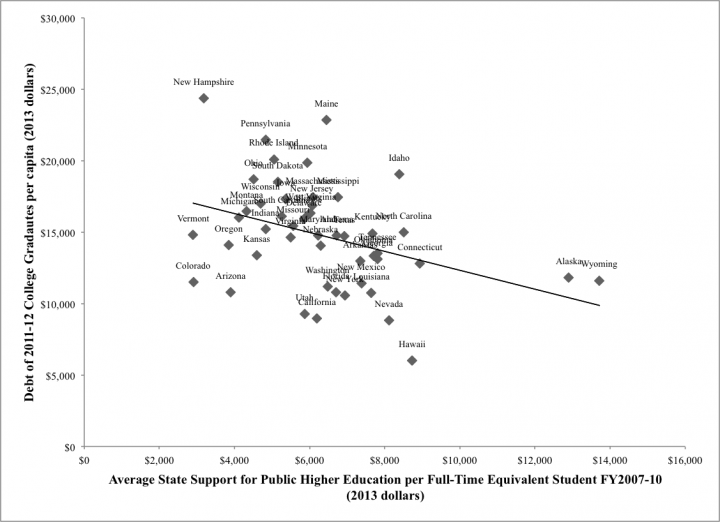

Our analysis of publicly available data shows that state support is linked to the amount of student loan debt at graduation. The chart below compares the amount of student loan debt at graduation to the level of state support across 49 states (data for North Dakota was not available.) The measure of student loan debt is the average amount of debt per college graduate from the 2011-12 school year. The level of state support is the amount of funds used to support public higher education per full-time equivalent student from state budgets averaged over four years. The four-year average is also lagged by one year to allow for any delay between changing state support and increases in tuition rates affecting students (Data sources: State Higher Education Executive Officers Association and CollegeInSight)

States allocating more funds per full-time equivalent student have a lower student loan burdens on a per graduate basis (a statistically significant relationship). The relationship also holds for graduates in previous years over the past decade. On average for every $100 in additional state support per student the loan burden at graduation declines by $66. And these figures include all students, those who borrow and those who don’t. The financial obligations for those who borrow, are much larger than the chart shows.

So far, debt hasn’t erased the value of a college degree, which has in fact reached record levels even when factoring in growing student debt. In the case of George Mason University, the comparatively high employment levels and wages of our graduates, our comparatively low tuition, and the fact that more and more of our students transfer from the community colleges and work during college have helped keep student loan default rates among the lowest in the country. We remain committed to finding alternative sources of revenue and efficiency to ease the burden on our students as much as we possibly can. But as the old saying goes, there ain’t no free lunch. If the state doesn’t pay, students likely will, either in the form of quality, or tuition, or time-to-degree or a combination of the above.