With Kirk Heffelmire

I was delighted to be invited by the Council of the Americas to speak at their annual conference this week. It is reassuring to see an impressive group of leaders from government, business and multilateral organizations appreciate the central role that higher education plays in driving integration and innovation, the themes of the conference.

Integration

Trade agreements are necessary but not sufficient to foster value-creating commercial ties. It takes many individual business leaders with the capability to reach across cultural and economic boundaries to create productive and sustainable partnerships.

Universities are uniquely equipped to educate that type of globally minded individual via our multitude of international programs and student exchanges. Yet, current numbers are still very low. The U.S. received almost 900,000 international students in 2014, yet it sent less than 300,000 students abroad (IIE data). International students filled 4.2% of American classrooms, but only 1.5% of American students went overseas, compared to the world’s 2% average (9.4% of American students will go abroad at some point before they graduate).

In addition to the relatively low numbers, the majority of Americans studying abroad do so for short programs (two months or less) and their destinations are not well aligned with the economic reality we live in. While China and Mexico are America’s second and third trading partners, they are only 5th and 15th among top destinations for American students. America trades less with the European Union than it does with China or Mexico, yet the UK, Italy and Spain alone account for about one third of all American students abroad, while China receives 5% and Mexico only receives 1.3% of them. Interestingly, the leading destination in Latin America is Costa Rica, which, with a population that is 4% of Mexico, manages to receive more than twice as many American students as Mexico does.

Earlier this week I spoke at the American Council on Education‘s summit on internationalization. I was impressed by the interest of many Latin American universities in increasing international activities. But I also noticed how suspicions around the fairness globalization and historic grievances still shape conversations in academia.

Innovation

Competitiveness in the 21st Century is driven by innovation. And universities are precisely engines of innovation.

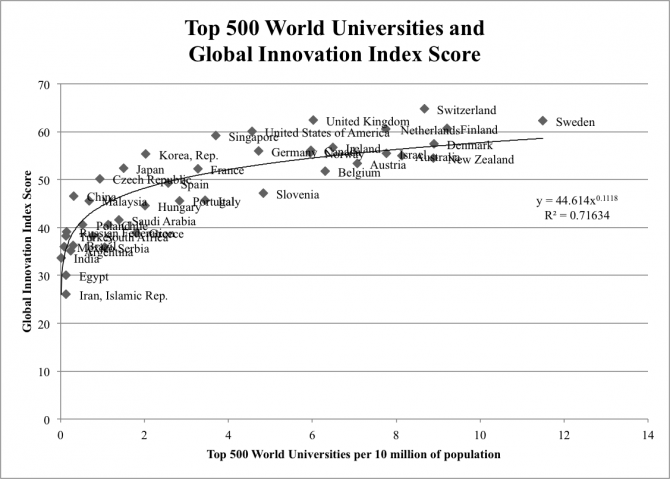

To illustrate this relationship, consider the Global Innovation Index ranking of countries by innovation capacity. The index is published annually by Cornell University, the global business school INSEAD, and the World Intellectual Property Organization. For 2014, the index theme was the human factors fostering innovation, which prompts exploring the relationship between top-ranked universities and innovation.

As posted previously here, the presence of top-ranked universities explains much of the variation in competitiveness across the world. The accompanying chart shows the relationship between innovation index scores and the world’s top 500 universities according to the Academic Ranking of World Universities. The presence of top-ranked universities (normalized by population) explains more than two thirds of the variation in innovation index score.

As posted previously here, the presence of top-ranked universities explains much of the variation in competitiveness across the world. The accompanying chart shows the relationship between innovation index scores and the world’s top 500 universities according to the Academic Ranking of World Universities. The presence of top-ranked universities (normalized by population) explains more than two thirds of the variation in innovation index score.

To be fair, the Global Innovation Index includes an assessment of higher ed, but it is only one of the seven factors it considers. The reality is, higher education has an impact on the other other components of the index, which is exactly why education is so influential in attracting and developing the best human capital.