Fundación Bankinter, an innovation think-tank sponsored by Spanish bank Bankinter and on whose board I serve, invited me last week to speak during in the occasion of its 10th anniversary celebration (in the photo, taken at the Telefónica center for innovation in Madrid, with Chris Meyer, Richard Kivel and Emilio Méndez). The topic couldn’t have been more timely and important in the Spanish context: education, technology and entrepreneurship.

Fundación Bankinter, an innovation think-tank sponsored by Spanish bank Bankinter and on whose board I serve, invited me last week to speak during in the occasion of its 10th anniversary celebration (in the photo, taken at the Telefónica center for innovation in Madrid, with Chris Meyer, Richard Kivel and Emilio Méndez). The topic couldn’t have been more timely and important in the Spanish context: education, technology and entrepreneurship.

My message was twofold: (a) higher education is crucial for competitiveness (in Spain and elsewhere), and (b) some of the most important interventions right now involve removing barriers to the inflows of talent.

I have made the argument here and in other settings that higher education is a key foundation of competitiveness in a world economy driven by innovation and global specialization/differentiation. The link between competitiveness and universities is multifaceted. Universities help drive productivity and innovation. They are sources of new technologies and incubators of new businesses. But they are also magnets of talent that can contribute to creating further economic opportunity. In the U.S., immigrants have played a key role in driving innovation and entrepreneurship. And, according to the Kauffman Foundation, the primary reason why foreign-born founders of American startups came to America, was to study.

At a time of tremendous budgetary constraints in parts of the developed world (Spain of course included), some of the most important and lowest cost interventions to support higher education and competitiveness would be to eliminate self-imposed administrative barriers to inflows (and even outflows) of talent. Spain’s system of college admissions, for example, are based on an idiosyncratic and cumbersome exam “selectividad“, which creates an often insurmountable barrier for would-be foreign students. Similarly, the Spanish system of faculty selection and promotion creates few if any incentives or decision-making autonomy for individual universities to compete for talent. In fact, a National system of habilitation and competitive exams, ironically established with the objective of creating a merit-based system, de facto creates often insurmountable barriers for the recruiting of foreign academic talent.

I recognize that promoting the import of talent at a time of high unemployment is as popular as promoting lower tariffs at a time of economic crisis. Protectionism, not openness is the natural reaction. And yet, it is precisely at times of crisis that talent and innovation are most desperately needed.

During the Q&A session, I was struck by Spanish entrepreneurs who continue to see hope in the future. It is individuals like them who will find personal opportunities at times like this and who, by doing so, will help drive Spain’s economy out of the hole.

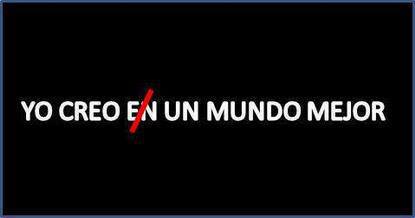

Their attitude reminded me of a meme a recently found on Facebook. It says in Spanish: “Yo creo en un mundo mejor”. With “en” it means “I believe in a better world”. Without it, it means “I create a better world”. In a way, an entrepreneur is the person who scratches the “en” in that sentence: who goes from believing in, to creating a better world.